I’ve written several times about the richness of the records at the Hagley Museum and Library for family history research, assuming you’re fortunate enough to have a family member that was associated with the duPont Company during it’s early years in Delaware. If your family did work in the duPont powder mills during the early-to-mid 1800s, or in one of the neighboring textile mills, there was a good chance that the children received their early education at the Brandywine Manufacturer’s Sunday School.

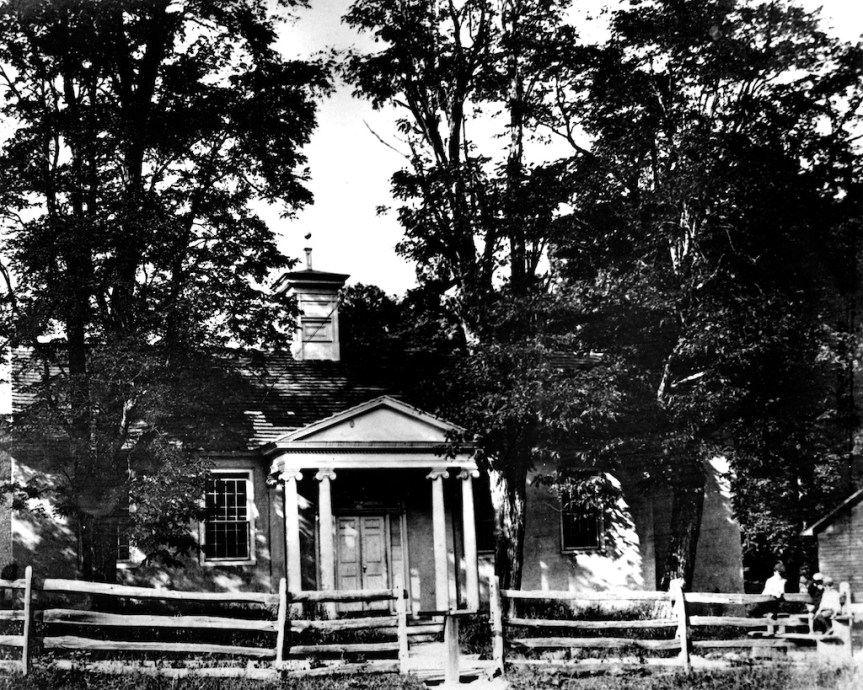

Brandywine Manufacturers’ Sunday School – Courtesy of Hagley Museum and Library

Organized in 1817 as a non-denominational school for children of local factory workers, it wasn’t a ‘Sunday school’ in the modern sense. Religion was taught there and all religions were welcome (even Catholics!), but the main focus was on providing children with the basics of reading, writing and arithmetic. It was a ‘Sunday’ school because class was in session on Sundays, when children were free from household chores and their responsibilities at the mills. The school was administered and lessons taught largely by the duPont women, most notably Victorine duPont Bauduy who dedicated herself to the school after the loss of her husband in 1812. The school was funded largely by the duPont company and subscriptions paid by the parents of the children.

The school was centrally located in the Hagley Yard and still exists today. The interior has been restored as a classroom and is open to visitors. During a recent visit, we listened to a short talk on the history of the school while sitting at the period school benches. We were also given an opportunity to attempt writing using a quill and bottled ink.

The school was centrally located in the Hagley Yard and still exists today. The interior has been restored as a classroom and is open to visitors. During a recent visit, we listened to a short talk on the history of the school while sitting at the period school benches. We were also given an opportunity to attempt writing using a quill and bottled ink.

Extensive records related to the school can to be found at the Hagley Museum and Library. The duPont company acted as a kind of bank for its workers – pay was credited monthly to the workers account and charges were withdrawn. The transactions might be simple withdrawals of cash for personal expenses, or they might be transactions between employees and others associated with the duPont community, such as the local doctor, company store, a boarding house or the Sunday School. These itemized transactions were maintained in the duPont Petit Ledger, which can be viewed in it’s original form at Hagley. In addition, many of the ledger pages can be searched and displayed online. Below is an excerpt from Daniel Toy’s account for 1820, showing a payment of 50 cents for ’S School Subscription’ on December 31. Also included in this excerpt is a payment of $1.87 to the company store (A. Fountain) and a payment of 31 cents to Dr. Didier for medicine. Daniel received $18 in pay for the month.

More important to family research are the school enrollment records. While I have seen portions of the records and taken a few notes, these records are not yet available online and are a bit difficult to work with. Thankfully, I recently received a detailed transcription of the records from Nancy Van Dyke-Dickison, a Toy cousin living in Washington State who is descended from Corneilius Toy (1813-1861).

These school enrollment records identify a registration number, the student’s name, year of first enrollment, the age at enrollment, their class number, and the parents name, occupation, religion and residence. In most cases, the record also includes a remark or two about when the child left the school and why.

I was able to find entries for seven of the first and second generation Toys living at Hagley or in the area. The oldest is for James A Toy. James A. was registration number 38 who came to the school in 1823 at age 10. He was the son of Daniel Toy (1789-1832), a Powderman and Catholic who was living at Hagley. James A. was in the 2nd Class. The remark for James A. is that he left school in 1831 and married in 1860 to McCullion (this marriage date does not agree with parish records).

Other records I found are for Daniel Toy’s daughters Jane, Mary and Nancy (Ann) and son Daniel. I also found records for James’ sons Daniel and (John) Thomas, who both entered the school in 1849. If anyone would like the details for these other records, just send me an email or leave a message in the comments. Thanks to Nancy Van Dyke-Dickison for sending me this information.

It’s interesting to note that the record for James A. Toy says he was age 10 in 1823, which would make his year of birth 1813 or 1814, depending on his enrollment month. His grave marker gives his year of birth as 1816 and says he was aged 65 years while his death notice gives his age as 66. Using the birth and death dates on the marker would make him aged 64 (and 9 months). In contrast, census records place his year of birth at 1820 or 1822, but I believe that folks tend to make themselves younger than they really are in the older census records. The last piece of evidence is a genealogy completed in 1941 by his grandson Eugene Toy (1904-1961), which gives his birth year as 1814. Personally, I’m going to trust Eugene and the school mistress, and give his date of birth as December 8, 1814.