It is true, that in a populous city, there must be taverns and houses for public accommodation – but are we bound to give every man who will not work a license to sell liquor?1

Very little was written about the drinking establishments along the banks of the Brandywine during the first half of the 19th century. There are no maps from the period showing tavern locations, no census records identifying tavern owners, no formal advertising of tavern licenses, no mention of property usage in deed records, and nothing of note in the local newspapers. However, the lack of specifics in the news and written records does not indicate a lack of interest in the drinking habits of the mill workers or in the ‘tippling houses’ where they exercised these habits.

Rough translation: “So what do you do with the rest of your time? Mr I, we have fun”

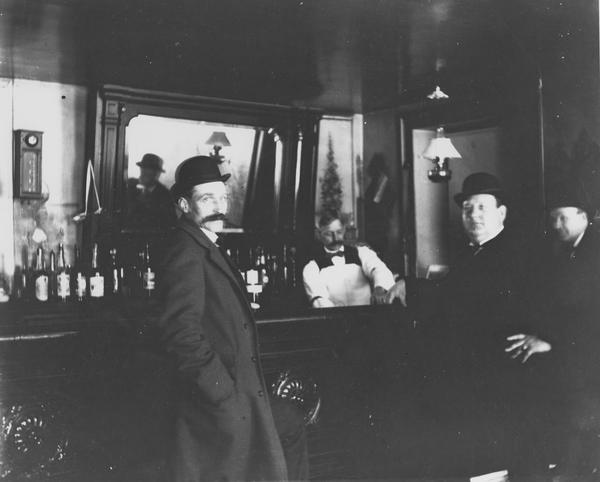

Image Courtesy of Hagley Museum and Library.